The tragic failure of the Sardoba dam has sparked fresh debate around water conflicts and the need for cooperation between countries in Central Asia

At 5.55 am on May 1, after five days of severe storms, a dam wall at the Sardoba reservoir in the region of Sirdaryo, Uzbekistan, collapsed and water poured through a breach onto cotton fields and villages.

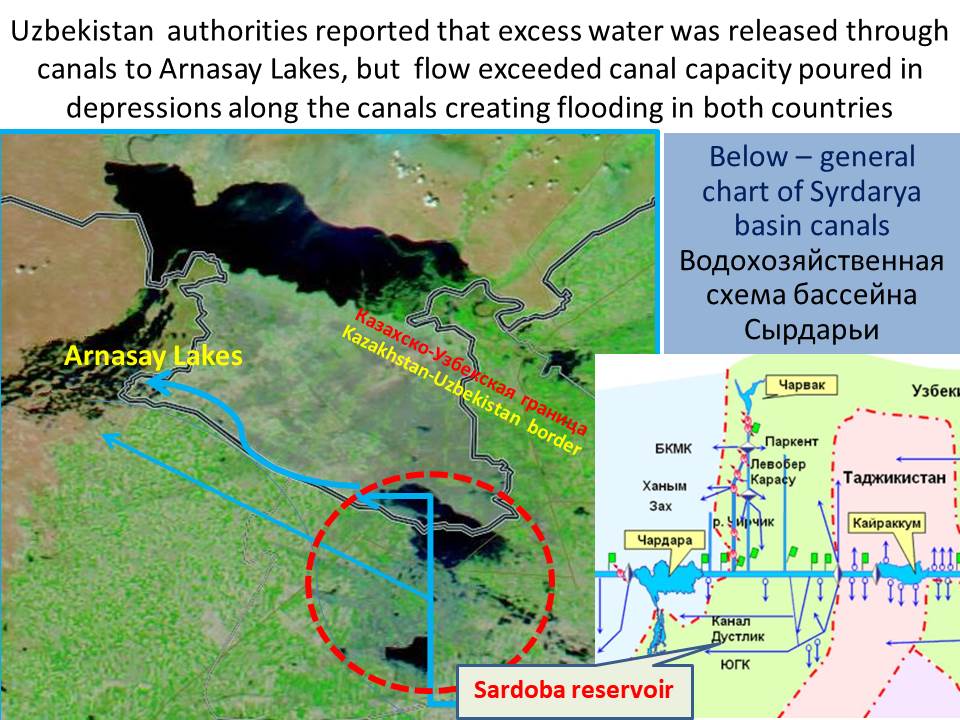

To reduce water pressure on the walls of the reservoir and prevent further collapse of dam walls, its gates were opened. Water spilled into the Southern Golodnostepsky Canal and its offshoots, with the intention of sending it to the Aydar-Arnasay lakes – a wetland of international ecological importance. The capacity of the canal was overwhelmed, and the flood expanded.

Victor Dukhovny, the director of the Scientific Information Centre of the Interstate Commission for Water Coordination (SIC ICWC) for Central Asia, said the volume of water lost could exceed 500 million cubic metres (m3) of the 922 million m3 the reservoir was designed to hold.

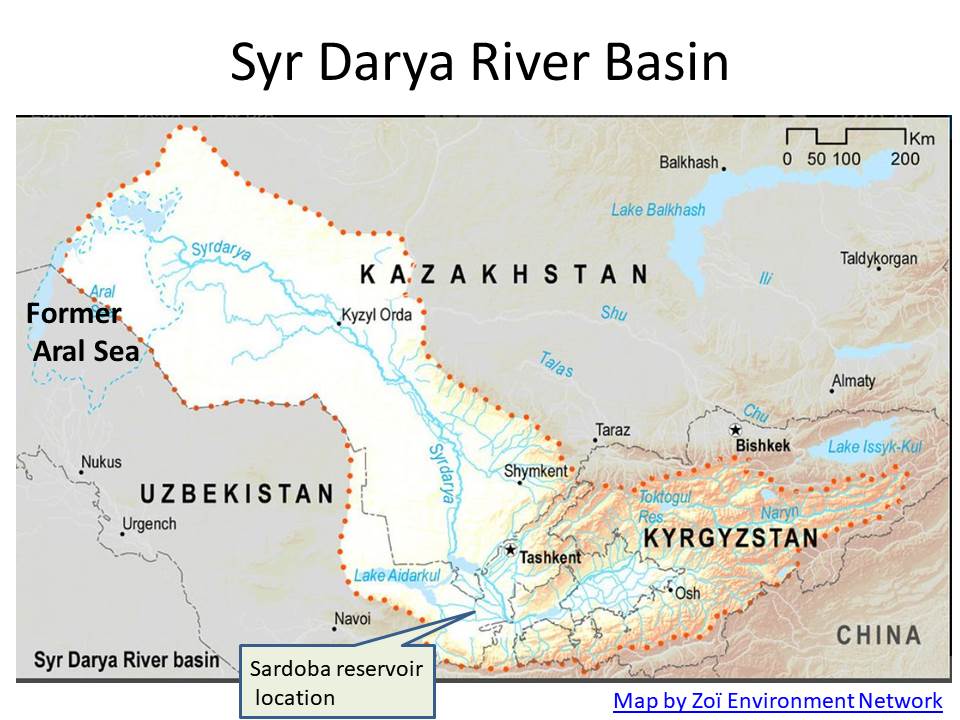

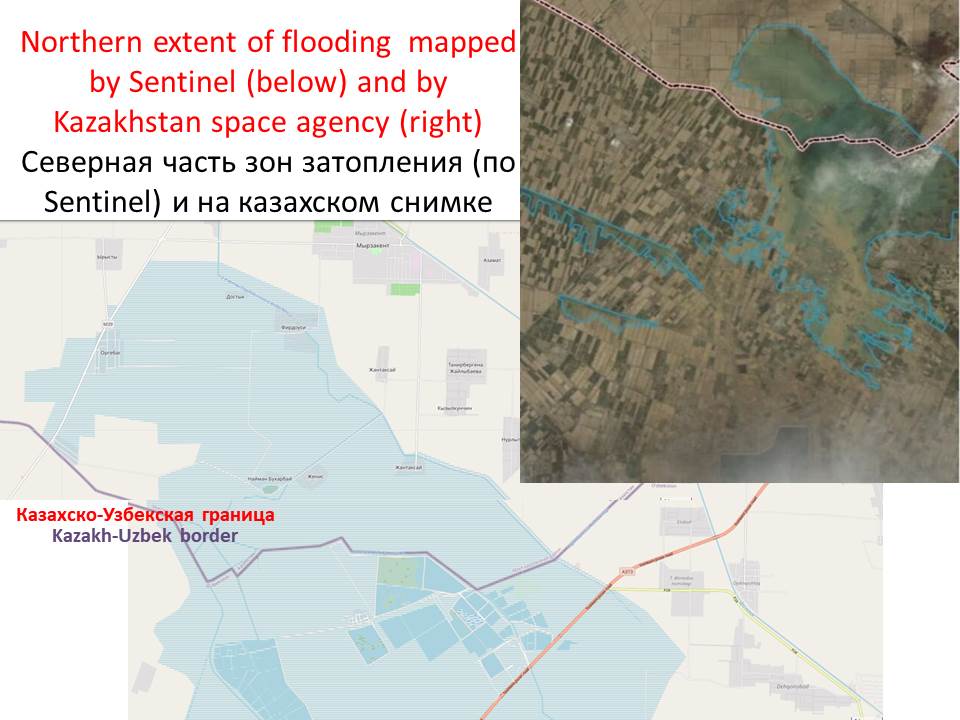

The flooding affected more than 35,000 hectares of land in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. Six people died and at least 111,000 were evacuated from the Syr Darya river basin. The cost of constructing the reservoir was 1.3 trillion Uzbekistani som (roughly USD 400 million in 2017); the recovery will require at least 1.5 trillion som, Uzbekistan’s ministry of finance has said.

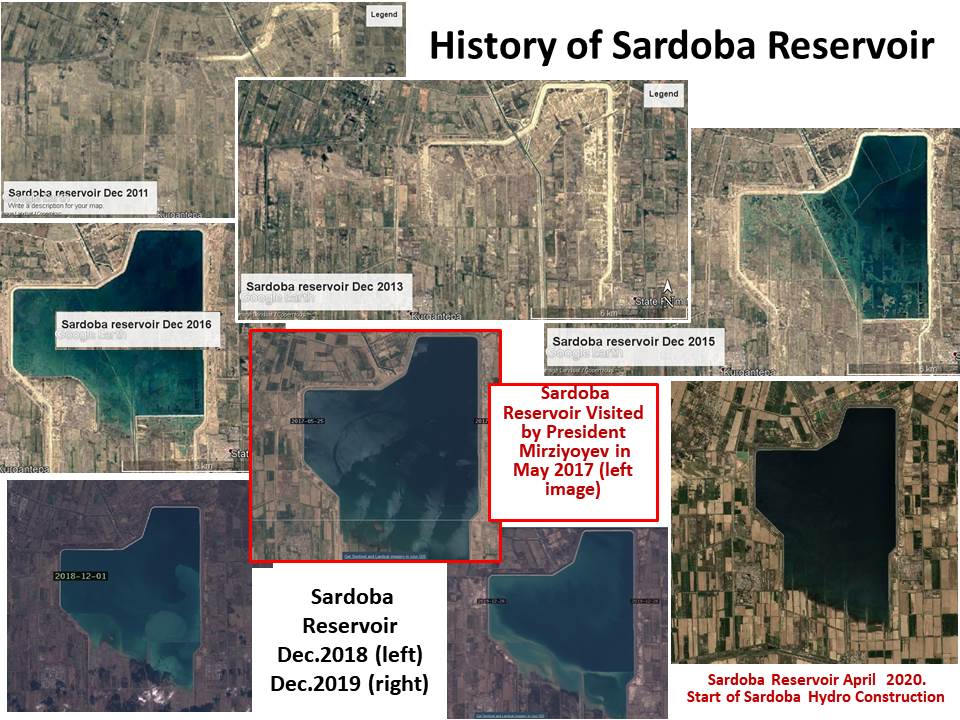

The Uzbek government has launched an investigation into the dam reservoir completed only recently in 2017, promising that “all those guilty… will be liable before the law”.

But whatever the immediate cause, the collapse of the dam is a culmination of decades of mismanagement and regional water conflicts in the river basin. The disaster has forced countries to cooperate over the immediate recovery and take first steps towards joint management of shared basins. However, it remains to be seen whether these intentions bear fruit.

The hungry grasslands

The Sardoba reservoir was built on a canal of an old transboundary irrigation system that straddles Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kazakhstan. The structure was planned back in 2008 and built in 2010-2017, with few official records available on the construction process and financing.

The plains where the Sardoba dam was built are known as the Golodnaya Steppe (which means ‘hungry grassland’ in Russian). They are naturally too dry to produce grain but were transformed during the Soviet era into an intensively irrigated agricultural area, producing grains and cotton, now one of Uzbekistan’s major exports.

In the 1940s, the Soviets developed Farkhad Reservoir, in current day Tajikistan not far from where the Sardoba reservoir is today. In the 1960s-70s they sent its waters into the Southern Golodnostepsky Canal. Dukhovny was in charge of that irrigation project. He recalled how difficult it was to build canals in some sections above treacherous layers of gypsum, a soft mineral found in sedimentary rock. Engineers had to put an extra layer of clay on the canal walls, which kept them safe for 60 years.

Despite this achievement, Uzbek hydro engineers considered the Golodnaya Steppe unsuitable for further water infrastructure development. Dukhovny said planning the Sardoba reservoir on top of a well-designed old canal system likely disrupted its functionality and contributed to the subsequent disaster.

Climate change could have also played its part in the disaster. Igor Shkradyuk, a renewable energy expert and head of industrial policy at the Biodiversity Conservation Centre, said, “Uzbekistan still uses calculations from Soviet times… But the climate has changed. For Central Asia, the main issue is the rapid melting of glaciers increasing river flow, but precipitation patterns have also changed dramatically. It is necessary to develop new hydrological models taking into account climate variability and upgrade hydraulic engineering structures to prepare for the greater likelihood of catastrophic floods.”

Legacy of Soviet water management

In Soviet Central Asia the irrigation of dry land was enabled by integrated water-energy management systems. The waters of the Syr Darya river were regulated by dams, including the giant Toktogul dam in Kyrgyzstan, prioritising supply for agriculture – mostly in Uzbekistan. The upstream republics of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan received fuel in winter to offset the hydropower energy they had agreed not to generate. The system looked perfect, but for one consequence: large scale water diversions have led to the disappearance of the Aral Sea, once the world’s fourth-largest lake.

In 1993, as the Soviet Union fell apart, the International Fund for Saving the Aral Sea (IFAS) was established. It aimed to coordinate water allocation and remediate environmental disasters across countries, with its key bodies stationed in Uzbekistan.

Cooperation deteriorated after independence because upstream countries started producing more hydropower in winter at the expense of water supply for irrigation downstream.

Dukhovny estimates that water shortages for irrigation in Uzbekistan amounted to 4 cubic km a year. As a result, large reservoirs, like Sardoba, were built in unsuitable places.

Uzbekistan’s first president Islam Karimov used harsh measures to retain his country’s water rights. He blocked supplies to neighbours who violated water allocation schedules, sent troops to secure reservoirs at borders, stalled reforms of IFAS and ICWC proposed by the Kyrgyz Republic and other countries, and even threatened military action in case of new dam construction.

Damming renaissance

When President Shavkat Mirziyoyev assumed office in 2016, he sought to reach out to his neighbours and restore collective water management, offering electricity purchases and joint dam construction to Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. While the political goal of this ‘hydro-détente’ was understandable, it was not based on any comprehensive assessment of the social, environmental and economic consequences of accelerated dam construction. There are already 60 large dams in the Syr Darya basin alone, capable of holding several annual river discharges.

Uzbekistan is also seeking to develop electricity sources for its growing economy. On May 12, 2017 at the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Forum, Mirziyoyev secured USD 2.7 billion from the Chinese Ministry of Commerce for a programme to repair and construct 32 dams. The general contractor and operator for the Sardoba dam was not a certified hydroengineering company, but a subsidiary of Uzbekistan Railways Company – a large state-owned enterprise involved in BRI developments.

On his return from the BRI Forum on May 17, Mirziyoyev inspected the almost-finished Sardoba reservoir. The project emerged into public view, with declarations it would enable two harvests of cotton and grain a year, aquaculture development and walnut plantations.

In an interview at the crest of the dam, the president declared that a new company, UzbekHydroEnergo, would be formed and a 15-megawatt (MW) power plant, Sardoba Hydro, attached to the reservoir. He stressed that the Chinese “tell us that time is money and ask us to complete faster, so that they can allocate (USD) 3 billion as soon as possible”.

Now, after the disaster, Mirziyoyev has appointed Abdugani Sanginov, an official involved in supervising the construction of the Sardoba dam, to the task force investigating its failure. Sanginov, who is also a senator, was assigned to lead UzbekHydroEnergo in May 2017, with responsibility for 37 existing hydropower plants and implementing vast hydropower construction plans. His son is head of Topalang HPD Holding, one of the main sub-contractors that built the dam.

Tensions with Kazakhstan

In rural Kazakhstan, around 32,000 residents were evacuated, two settlements destroyed beyond repair and three others flooded. Total losses just in agriculture exceeded USD 10 million.

On May 5, Sergei Gromov, Kazakhstan’s vice-minister of ecology, said, “The construction of the indicated reservoir was not agreed with us (as required by treaties)… We insist that the dam is not restored at all, if it is restored, then in smaller volume.”

Mirziyoyev reacted immediately. “We very much regret that this unexpected technological disaster has caused so many troubles and damage not only to our population, but also to our neighbours, our brothers… I assure you that all those guilty, regardless of who they are and what position they hold, will be liable before the law,” he said. Uzbekistan sent heavy machinery to Kazakhstan to help with disaster-relief efforts.

On May 25, the Kazakh government posted for public comment a draft treaty proposing a bilateral commission on transboundary water bodies. It listed several cooperative activities, including information exchange, joint decision-making and financing infrastructure. Provisions for environmental quality, environmental impact assessment and preservation of shared aquatic ecosystems were glaringly absent.

The draft agreement was removed from the official website before June 2. This could be a sign of political tensions either with Uzbekistan (which could take publication of a draft as unfriendly pressure) or between different Kazakh agencies.

Some Kazakh environmental experts saw the document as a sign of progress. Bulat Esekin, a member of the working group on drafting the Kazakh State Programme on Water Resources Management, noted, “For Syr Darya we need such bilateral treaties open to accession by other countries, which should be based on IWRM [integrated water resources management] principles and incorporate the key issues of water quality and ecosystem resilience.”

A last chance for the Aral Sea?

The Sardoba disaster is the result of lack of consideration of climate change, 100 years of basin-scale environmental mismanagement and 30 years of water feuds, coupled with demand for quick political results, instead of scientifically based and publicly discussed decision-making.

This could be a chance to reverse the destruction of Central Asian rivers. What happens next depends largely on how Mirziyoyev responds to the failure of the reservoir.