As President Xi Jinping calls for greater environmental protection, officials are eager to demolish badly-planned dams. But the country will need vast amounts of clean hydroelectric power to meet its net-zero goal.

China is trying to wean its massive economy off coal and fossil fuels to meet its ambitious goal of becoming carbon neutral by 2060. So why is it trying to shut down as many as 40,000 hydropower plants?

The answer lies deep in the nation’s troubled history of trying to control its rivers. Ever since Chairman Mao Zedong exhorted workers in the 1950s to “conquer nature,” China has been throwing up dams large and small at a prolific rate to generate power, tame flooding and provide irrigation for fields and drinking water for cities. The long-term effects of that often chaotic policy are now coming home to roost.

Many dams in the country are too small to generate meaningful amounts of power. Others have simply become redundant as their rivers ran dry, their reservoirs silted up or they were superseded by dams built upstream. “For a long time, people thought it was a waste to let the river just run away in front of you without doing something,” said Wang Yongchen, founder of Green Earth Volunteers, a Beijing-based non-governmental organization that focuses on river protection.

In a western suburb of Beijing, one of the nation’s most famous early hydropower projects is being turned into a tourism site. Workers are busy paving roads and beautifying houses at a new “ancient business street” near the retired Moshikou station. Built in 1956, the 6,000 KW project in Shijingshan, Beijing’s former industrial center, was the first big automated hydro station designed and built independently. It was constructed on a diversion canal of Beijing’s “mother river,” the Yongding, the capital’s main source of drinking water until the water became too polluted in the 1990s, and was a source of pride for the new People’s Republic.

Moshikou never officially ceased operation. It just gradually stopped generating power, a victim of worsening droughts in the north of the country and increasing demands on its waters from towns and villages upstream that built hundreds of barriers to harvest its water. More than 80 water conservancy projects were built in the Beijing region alone, according to Chinese local media.

By the 2010s, the river was running dry an average of 316 days a year.

“The weather in Beijing has changed,” said Jin Chengjian, 60, who spent all his life in Shijingshan district. “As a child, I often swam in the diversion canal near the station. Now, the water gets less and less, and dirtier and dirtier.”

Moshikou’s proximity to the capital has given it a new lease of life, but many of China’s old dams have not been so fortunate. In Weizishui village, 90 minutes’ drive upstream, a 68-meter tall concrete dam was completed in 1980 to control flooding. It took six years to finish and was never needed once.

“Bad planning,” said local villager Gao, 75, who like many Chinese people declined to give his first name. “It could just collapse one day, so I never go too close.”

Last year, the government blocked the only access route to the dam for “virus prevention.” The structure had been attracting social media pundits who compared it with the Hoover Dam in doomsday movies.

The scale of China’s dam-building frenzy is hard to grasp. By the end of 2017, China’s longest river, the Yangtze, and its tributaries had more than 24,000 hydropower stations spread over 10 provinces. At least 930 of them were constructed without an environmental assessment.

Many old dams pose serious safety threats, especially during summer floods. According to China’s Ministry of Water Resource, 3,515 reservoirs burst between 1951 and 2011. They include the infamous Banqiao dam in Henan province which, along with another 61 dams, broke after six hours of torrential ran in August 1975, killing 240,000 people.

Dams still fail in China. Earlier this year, two in Inner Mongolia gave way in heavy rain. In floods that killed more than 300 people in Henan this summer, the army warned that the Yihelan dam “could collapse at any time.”

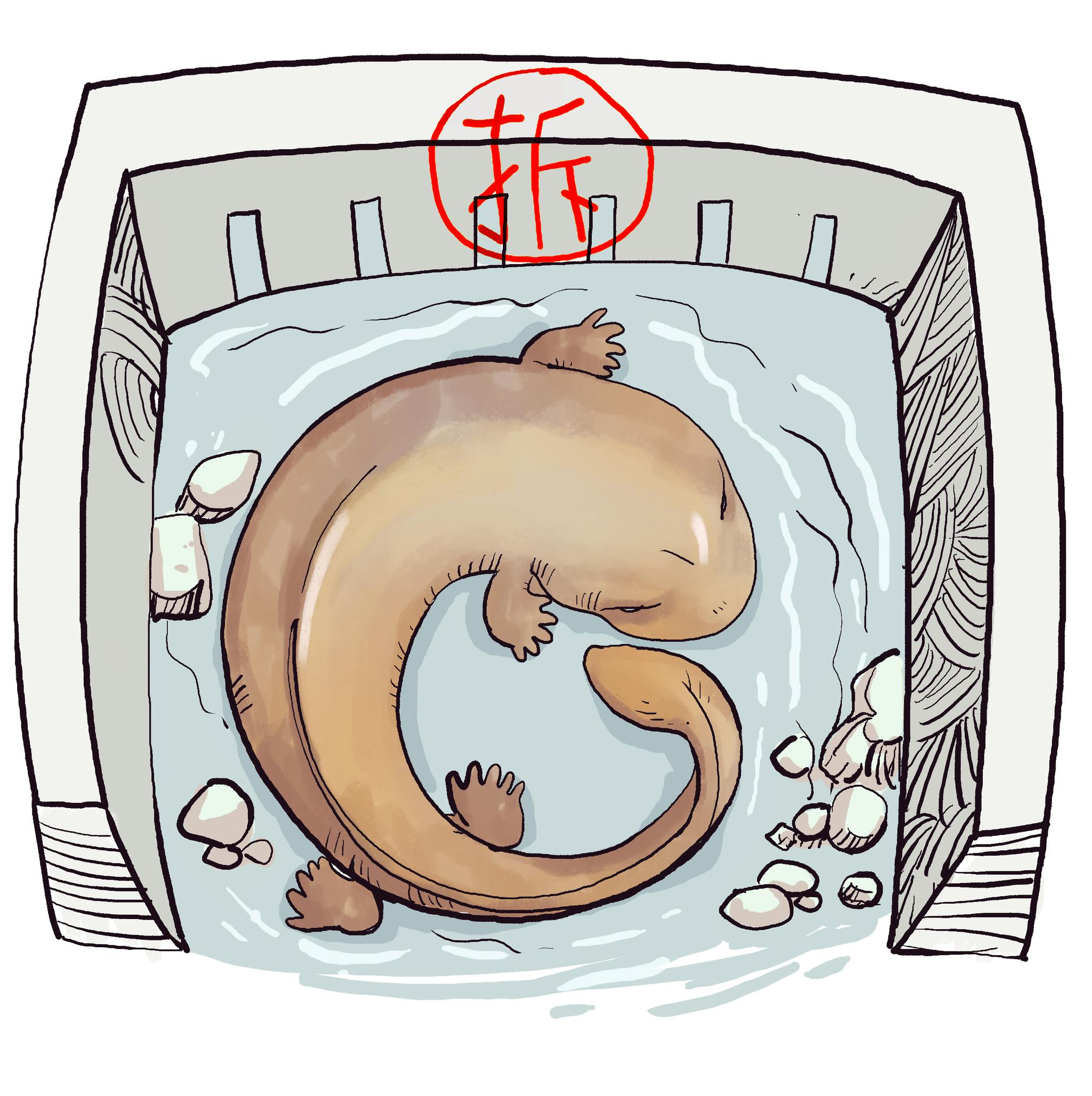

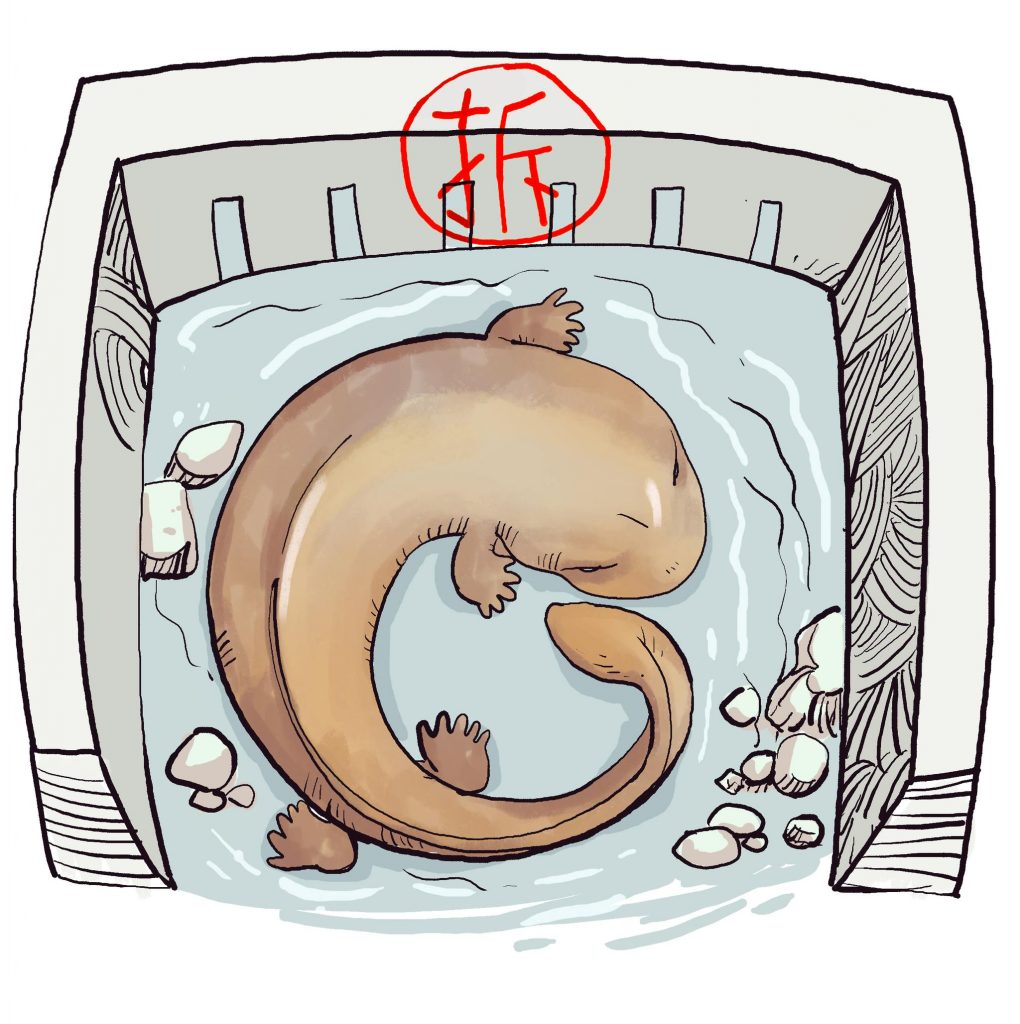

Large dams and their reservoirs are also increasingly criticized for environmental damage. They alter the flow of rivers, submerge habitats and disrupt the migration and spawning of fish. Since the mighty Three Gorges Dam was completed on the Yangtze in 2006 after two decades of construction, several lakes downstream that absorbed the river’s overflow, have shrunk dramatically or disappeared.

China continues to build big water projects, including the 16GW Baihetan hydropower project that opened in time for the Chinese Communist Party’s 100 anniversary this year. But the government has said it wants to halt the development of smaller ones. In the 13th Five Year Plan for the hydropower industry starting 2016, the government for the first time said it would “strictly control the expansion of small hydropower stations” to protect the environment. In 2018, after Xi visited the Yangtze region and Qinling mountains in the northwest and called for better environmental protection, a national campaign was launched to remove or improve 40,000 small hydro stations.

“Our rivers are over-exploited after decades of constructing without proper planning,” said Ma Jun, director of the Institute of Public & Environmental Affairs.

But proponents of hydropower say more is needed, not less, to help wean the country off fossil-fuel energy. “Provinces are applying the ‘one size fits all’ approach now, and officials consider demolishing large amount of projects as an achievement in their careers,” said Zhang Boting, deputy general secretary of the China Society for Hydropower Engineering. “It should not be like this. We should remove coal projects first, not hydropower which China needs to become carbon neutral.”

A further problem is who will pay to get rid of the unwanted projects. Closing down a hydropower plant is one thing, but removing a dam, especially a large and potentially dangerous concrete structure, is a major engineering project.

Zhouzhi county in Shaanxi province in the northwest owes over 100 million yuan ($15.5 million) to a company that agreed to demolish three hydro stations. The county’s revenue for the first half of 2020 was only 135 million yuan, and it has another 26 hydro plants that need to be removed. In many places, due to the costs of demolition, only the hydroelectric turbines have been removed. The dams remain.

“China benefited so much from decades of water conservancy projects,” said Ma, from the Institute of Public & Environmental Affairs. “Maybe it’s time for the industry to pay back for the environmental restoration.”

Few of the projects enjoy the government funding and attention lavished on Moshikou, the future tourist attraction, which is part of a Yongding River Culture Belt being built by Beijing. Among the belt’s famous industrial sites is the Beijing Capital Steel Factory, once the nation’s biggest steel mill and now home to the 2022 Winter Olympic Games Committee. On a weekday morning, people jog and play badminton in the park or fish in the dam’s Sanjiadian reservoir. Antique sellers set up stalls beside the old hydropower station, repainted in white and cream for the Party’s centenary.

The reservoir is full again, not because the Yongding River has recovered, but because of an almost $4 billion water diversion project to “restore the ecological environment.” The water comes from the Yellow River, the country’s second-longest waterway. It’s also one of the most stressed bodies of water in the country, and tends to run dry. “The government has spent a lot of money, but only to solve superficial problems — to make the river look good, rather than addressing the ecosystem,” said Wang. “We shouldn’t solve one river’s problem by putting pressure on another river that’s also in trouble.”

Source Bloomberg